One of the things that has stuck with me after meeting with HP last month is that the movie industry is going through a lot of changes. It seems to me that few consumers have any concept of how much this industry is likely to change by the end of the decade. So this week, I thought it might be interesting to explore the technology changes that are coming — from creation to delivery — and revisit why it might take some time for us to see the full potential of these changes exhibited in the market.

While movies like Shrek are clearly artificial, it is amazing how many of the movies since Jurassic Park have been based largely on actors and blue-screen technology. In the Matrix and Spiderman, for example, much of the action is animated even though it appears real. It won’t be long until we have our first fully animated movie that doesn’t look animated at all. We’ve certainly seen dead actors digitally transferred into current commercials, and I’ve begun to wonder what this virtualization means, long-term, to the movie industry. For instance, do we really need actors anymore?

We’ve been able to synthesize voices for some time, and we can almost create the perfect voice for a certain situation. I’ve done some voice-over work for fun, and I can tell you that you still need a live voice or it just doesn’t sound real. But that will change. So while the physical representation of a person can be virtualized at this point, we still can’t virtualize voices reliably just yet. But even that is likely to change.

The Do-Over

One of the most disappointing movies for me this summer was the Chronicles of Riddick. I had picked up the novelization for the movie and was incredibly eager to see the film after reading what, to me, was a great story. But the movie seemed flat, probably because they pulled out the parts that made you care about the characters. They never did explain the “why” behind the story, which turned the movie into a bunch of loosely coupled action sequences. Like diet cola, it wasn’t particularly satisfying.

Adding those sequences back digitally might have turned a marginal movie into a good one, maybe even a great one, but we’ll never know because the studio didn’t fix the problem. They could do this by the time the DVD comes out, but they clearly missed an opportunity with the initial release.

When using a new technology, people often get stuck doing things the way they did before that technology actually existed. I have this problem myself when doing a taped interview. In a taped interview, there are “do-overs,” but I often do them in one take when it clearly would be better if I took the opportunity to fix a misstatement.

The tools the movie industry is using now should allow, for many movies, the opportunity to pull the movie back in and fix it rather than let it die in the theaters, but it may take some time for the industry to realize and adjust for this.

Regionalizing Movies

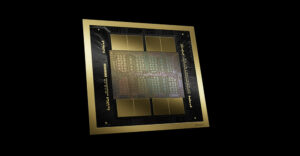

Part of what is going on between DreamWorks and HP is the full digitization of the process. From cradle to grave, eventually, the film will be digital. By the end of the decade, these digital films might be correctable even after they have been received for showing in the theaters.

Because they’ll be so editable, you might even be able to regionalize them by showcasing a local city as the backdrop or local celebrities as background in the film. Because product placement is already a big trend in movies — which becomes a problem for products that aren’t offered worldwide — regionalization could allow for better product placement and lower-cost films.

Forget theaters; think of what the cable providers could do with this.

Now, if we think about actors, wouldn’t it be great if the actors in a movie looked more like the citizens in the country the movie is playing in? China is ramping up a movie industry. You would think that movies with European, rather than Asian, casts and stars might be better accepted in some demographic areas. This could become the next big outsourcing craze.

Movies as a Cottage Industry

With the technology needed to create realistic virtual films continuing to drop in price, there is an increasing opportunity for low-budget films. If you have never been to Atom Films you should go for a visit.

From cartoons to more traditional venues, Atom has a collection of short films done on low budgets. These films can give you a feel for where the entry-level technology is. With a little imagination, you too can see where this is going. While the major studios try to figure out how to address the online market, Atom is doing that today. Many of these films are actually very entertaining.

Even moving further down-market, a little start-up in Silicon Valley — a firm called Valux has introduced a product, MinutePitch, that allows you to take the raw videos that some cell phones and digital cameras create to produce video marketing collateral and measure the success of that collateral.

While this is a far cry from movies today, the success of software.com shows that we are clearly moving into a period where ISVs are once again popular. Putting the production and distribution facilities for movies on the Web is an interesting concept for the future.

Shifting Costs to Creativity

Once the entire cradle-to-grave process is digitized, there should be a cost shift that puts much more of the effort into telling the story in a film and much less into the production of it.

I’ve spoken about the changes Microsoft was making in gaming tools, and I’ve also spoken about the growing similarity between the creation of games and movies — right down to the cost and use of actors.

Much as software tools are being modified so that game production now can be automated, the same process is going on with the creation of movies. In some cases it might even be the same tools used in both industries. The end result should initially be better movie modeling — the death of story boards — and, coupled with the do-over feature, eventually the near elimination of expensive bad movies.

Distribution of the Future

Distribution models are clearly broken, but I’ve been looking at what has been called the real iPod killer: the Janus technology from Microsoft. This new technology, initially targeted at music, allows you, for a monthly fee, to access the full library of content and the ability to download that content onto any compliant device for unlimited use as long as the subscription is valid.

With a hard-drive based player, you would no longer need to buy films or CDs — or even pay by the song — which should have some interesting long-term implications for a lot of things.

While currently downloading a film on DSL or cable broadband takes about half the film’s running time, this time delay will drop with increased bandwidth. And if you have access to the entire library, you could download several films at night to watch at your leisure.

While the “when” part of Janus still remains a question today, it won’t be a question by the end of the decade. Services like Janus will probably mean the end of companies like Blockbuster and Netflix unless they can adapt to the new technology.

My guess is that in 2010 I’ll be able to watch any movie I want from wherever I am. I might actually be able to create some of them myself, and I might get to enjoy actors who are not only no longer living but who might have never been born in the first place.

Despite all of these developments, how much do you want to bet that some 2010 kid will still be complaining that there is nothing interesting to watch?

Rob Enderle, a TechNewsWorld columnist, is the Principal Analyst for the Enderle Group, a consultancy that focuses on personal technology products and trends.