A med-tech startup has developed a fast and easy way to treat certain burn wounds with stem cells.

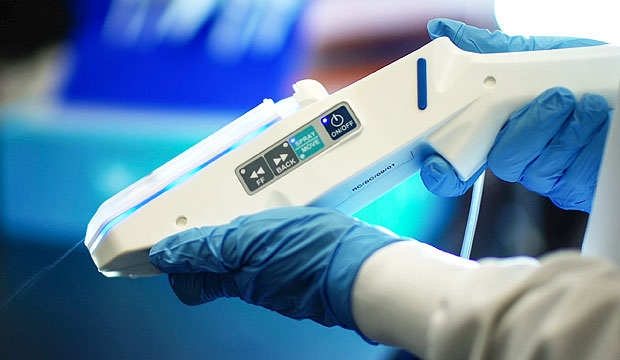

RenovaCare harvests a variety of cells, including stem cells, from a healthy area of skin on a patient. Those cells are then suspended in a water-based solution, which is loaded into the company’s SkinGun and sprayed onto the wound.

“The sprayer allows us to have a generous distribution of cells on the wound,” explained Roger Esteban-Vives, director of cell sciences at RenovaCare.

The procedure takes about 90 minutes.

“It’s gentle, and the skin that regrows feels and functions as the original skin that it replaces,” said RenovaCare CEO Thomas Bold.

RenovaCare’s CellMist method gets a greater yield from its harvest than mesh grafting, a more common way to treat burns. At a maximum, grafting can treat six times the size of its harvest area. CellMist can cover 100 times its harvest area.

“That’s why our skin sample can be so small,” Bold told TechNewsWorld. “Depending on the size of the wounded area, we’re talking about postage-stamp-sized.”

Alternative to Skin Grafts

Using stem cells to treat some types of burns is a promising alternative to skin grafting, which involves removing large sheets of healthy skin from a patient and puncturing it in a grid-like pattern to form an expandable mesh that’s stitched to the wound.

“The [skin-graft] procedure is extremely painful,” said Bold.

What’s more, an additional wound is created in the place where the healthy skin for the graft was removed.

“That often results in poor cosmetic outcomes, with scars and deformed skin,” Bold pointed out.

Other drawbacks of skin grafting include restricted joint movement and the inability of the skin to grow with a patient.

“For a kid,” Bold noted, “that means ongoing new surgery as the kid grows.”

Mesh graft patients can require months of physical therapy. They also can face ongoing problems ranging from the psychological impact of permanent disfigurement to risk of addiction resulting from long-term pain management with pain killers.

High-Cell Viability

A key to the effectiveness of RenovaCare’s treatment is its high rate of cell viabililty.

When dispensing cells over a wound, it’s important that they make the transition without being damaged. Damaged cells reduce the effectiveness of the treatment.

Ninety-seven percent of the stem cells in RenovaCare’s SkinGun remain viable after being sprayed on a wound, according to the company.

High cell viability also contributes to faster healing. When a wound heals naturally, cells migrate to it to build up the skin. That process can take weeks.

“What we do is isolate the cells from a healthy area, spray them on the wound, and accelerate the healing process,” Esteban-Vives told TechNewsWorld.

“With the stem cells, we create thousands of regenerative islands all over the wound and close it with an epithelial layer,” Bold explained. “Once that layer is closed, the wound is dry and considered healed.”

After that, the cosmetic healing will take place naturally.

Time is important for wound healing.

“Our patients’ wounds could heal over time,” Esteban-Vives said. “The problem is that during that healing time, complications can occur. Infections, contractions and scar formation could happen.”

Patent Challenged

The CellMist System hasn’t been approved yet for clinical use in the United States, although it has been used on thousands of patients on an experimental and innovative practice basis, Bold noted.

The company is awaiting FDA approval of its CellMist System so that it can begin clinical trials.

The FDA isn’t the only hurdle for RenovaCare to clear on its road to bringing its medtech to market, however.

Avita Medical has challenged one of RenovaCare’s patents. Avita also makes a skin regeneration system that sprays a patient’s cells on a wound to heal it.

Avita last month filed a challenge against RenovaCare with the U.S. Patent and Appeals Board, which will decide if the dispute between the firms should be taken to court.

“We believe we have presented a very strong rationale to the PTAB,” said Avita CEO Adam Kelliher, “as to why this patent should never have been issued.”