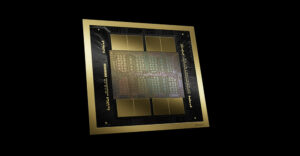

IBM researchers, in collaboration with the Fraunhofer Institute in Berlin, have prototyped a new method for cooling microprocessors stacked on top of each other, creating a 3-D processor that could keep Moore’s Law running strong for the next decade. Key to the effort is water, which seems to be the only material that can keep the stack from burning up.

“As we package chips on top of each other to significantly speed a processor’s capability to process data, we have found that conventional coolers attached to the back of a chip don’t scale. In order to exploit the potential of high-performance 3-D chip stacking, we need interlayer cooling,” explained Thomas Brunschwiler, project leader at IBM’s Zurich Research Laboratory.

“Until now, nobody has demonstrated viable solutions to this problem,” he added.

Hotter Than a Hot Plate

3-D chip stacks would have an aggregated heat dissipation of close to 1 kilowatt — 10 times greater than the heat generated by a hotplate — with an area of 4 square centimeters and a thickness of about 1 millimeter, IBM reported.

IBM’s answer is to create many tiny channels as thin as a human hair for water to flow through between the chip stacks, getting the water extraordinarily close to the source of heat.

“This truly constitutes a breakthrough. With classic backside cooling, the stacking of two or more high-power density logic layers would be impossible,” noted Bruno Michel, manager of the chip cooling research efforts at the IBM Zurich Lab.

Test Prototype

In the experiments, scientists piped water through a square-centimeter test vehicle, consisting of a cooling layer between two dies, or heat sources. The cooling layer measured only about 100 microns in height and was packed with 10,000 vertical interconnects per square centimeter, IBM reported.

The team overcame key technical challenges in designing a system that maximizes the water flow through the layers, yet hermetically seals the interconnects to prevent water from causing electrical shorts. IBM likened the complexity of the system to a human brain in that millions of nerves and neurons for signal transmissions are intermixed but do not interfere with tens of thousands of blood vessels for cooling and energy supply.

The scientists drilled holes through the layers for signal transmission. To insulate these “nerves,” scientists left a silicon wall around each interconnect — also called “silicon vias” — and added a fine layer of silicon oxide to insulate the electrical interconnects from the water. The structures had to be fabricated to an accuracy of 10 microns — 10 times more accurate than for interconnects and metallizations in current chips.

“Having water cooling in between chip layers is a challenge since we have to make sure that the through-silicon vias are safely isolated from the water,” Michael Loughran, IBM communications manager for IBM Research, told TechNewsWorld.

“We have developed a bonding technique that creates the electrical connection and at the same time provides a sealing ring,” he explained.

In the final setup, researchers placed the assembled stack in a silicon cooling container resembling a miniature basin, then pumped water through the chip layers.

“We envisage this to hit the market with high volumes in about 10 years from now. In the meantime, we are seeking some niche applications to allow us to create a mature technology. [The] first niche applications will be around in five years,” Loughran said.