Following a day’s delay due to cloudy weather, space shuttle Endeavour launched successfully early Monday morning from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The shuttle, which launched at 4:14 a.m. EST, is carrying a new module and an attached cupola for the International Space Station (ISS).

“What a beautiful launch we had this morning… the orbiter performed extremely well,” said Bill Gerstenmaier, associate administrator for space operations, during the postlaunch news conference. “This is a great start to a very complicated mission.”

Docking Over Spain

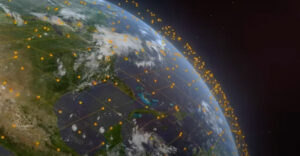

Commander George Zamka, Pilot Terry Virts and Mission Specialists Kay Hire, Stephen Robinson, Nicholas Patrick and Robert Behnken began their 13-day mission, officially known as “STS-130,” with an eight-and-a-half-minute dash to orbit, lighting up the central Florida coast as Endeavour arced to the northeast en route to space.

When Endeavour lifted off, the ISS was traveling at almost five miles a second about 212 miles over western Romania. Endeavour is scheduled to dock with the station at 12:09 a.m. Wednesday over the northern coast of Spain.

Three spacewalks are planned during the voyage to install the Tranquility node and cupola on the ISS. The seven-windowed cupola will be used as a control room for robotics; together, the new components are designed to further space-based study of the Earth.

4 More Missions

STS-130 is the 32nd shuttle mission to the ISS and the last scheduled nighttime launch in shuttle program history.

Still to come are four more shuttle missions before the program draws to a close at the end of this year.

The next mission — STS-131, scheduled for March — will deliver research and science experiment equipment, a new sleeping area, and supplies to the ISS in a logistics module carried in the shuttle’s payload bay.

Following that are STS-132, planned for May, which will deliver an integrated cargo carrier and Russian-built mini research module; STS-134, which is scheduled to deliver the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer in July; and STS-133, planned for September, which will deliver critical spare components.

STS-133 will be the 134th and final shuttle flight, as well as the 36th shuttle mission to the station. After that point, trips to the ISS will involve relying on other countries for transportation or traveling on forthcoming commercial spacecraft.

‘A Mistake from the Beginning’

“The space shuttle program was a mistake from the beginning,” said Randa Milliron, CEO and cofounder of Interorbital Systems and Trans Lunar Research.

Interorbital Systems is a rocket and spacecraft manufacturer that hopes eventually to provide commercial space transportation.

When the U.S. government destroyed the old Apollo program and replaced it with the much more expensive space shuttle program instead, it “destroyed what was a viable manned space program” and “set us back decades in terms of our exploration,” Milliron told TechNewsWorld.

“The shuttle was far too expensive for what it delivered,” she added.

Orbital Tourism in 2012

While Milliron views the new need for commercial services as an opportunity, it might have been better to provide some kind of interim service for travel to the ISS without making the U.S. entirely reliant on global sources until commercial alternatives are available, she noted.

Interorbital Systems anticipates that it will begin offering orbital tourism trips on a two-person capsule in 2012, Milliron said. Such a journey would involve about eight orbits and 12 hours of travel, she explained, but it would not go to the ISS.

For that, Interorbital Systems is building a six-person capsule for cargo and travelers that could be ready as soon as 2013, she said.

‘Not the Best Devices to Have in Space’

“By putting huge amounts of money into going into space, we were not putting it in a direction that was going to pay off very much,” Neville Woolf, University of Arizona professor emeritus of astronomy, told TechNewsWorld.

Neither the administration nor the general public have “come to terms with why humans are not the best devices to have in space in the long run,” Woolf added. “People are still talking as if we haven’t realized the immense volumes of space and vegetation that it takes to keep people alive.”

A better approach, Woolf contends, is to focus on robotics, but that’s an area in which “we just haven’t gotten as far as we should have,” he said.

‘We Forgot What It Takes to Be First’

Indeed, if nothing else, it’s clear the U.S. space program has much work to do in the years ahead.

“We forgot what it takes to be first,” concluded Paul Czysz, professor emeritus of aerospace engineering at St. Louis University.