The current dustup between Apple Pay and CurrentC is a stark, bleak mess. That’s not because Apple promises an easier, more secure way of making a smartphone-based retail transaction. Nor is it because CurrentC wants to harvest data on you and provide behavior-bending coupons, incentives and special deals, while cutting out the middleman credit card processing industry.

If you think those three sentences are complicated, it gets worse. Paying by smartphone — which seems like a new and cool convenience — is just the start of an unavoidable new in-person retail experience.

Solving 1 Problem to Create Many

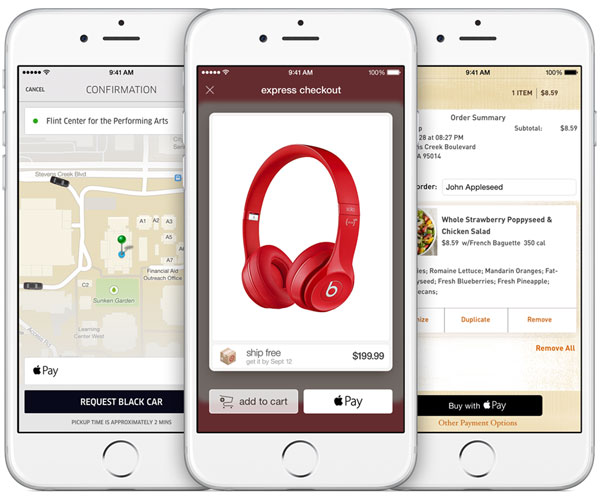

Let’s start with Apple Pay. It’s a secure and quick method of making a payment to a merchant using your iPhone 6, 6 Plus, or in the future, an Apple Watch. What if you don’t have one of those devices? Too bad for you. Will Apple ever roll out Apple Pay to any non-Apple device? Not likely anytime soon.

Because so many retail merchants now have near-field communication point-of-sale terminals, Apple Pay doesn’t hurt those who choose to use non-Apple devices — and it doesn’t exclude merchants from accepting other NFC-based forms of payment using other devices.

The feature is exclusive to Apple customers… but it’s just another form of payment that comes with some nifty benefits that fans of privacy and security appreciate. It’s like handing a store clerk a gift card. Easy. Secure. Anonymous. Nice.

As for security, Apple Pay keeps your credit or debit card number out of the hands of merchants. That’s all well and good. Even some of the largest and most well-funded retail organizations have seen massive breaches of stolen data.

Next, it’s so secure that you don’t have to sign anything. In fact, you don’t have to whip out another form of ID, like a driver’s license, which typically has your physical address on it. You don’t even have to let the merchant know your name.

Is it much faster than swiping a credit card? Usually.

Seems like Apple Pay is all goodness and light, right? It brings a better way of making payments but doesn’t stop any other method of payment a consumer or merchant might want to embrace.

Enter CurrentC

CurrentC is run by MCX, which has a bunch of retail members — the most prominent among them Walmart. Of course, CVS and Rite Aid are the members that started accepting Apple Pay then realized they had to stop because of their agreements with MCX around CurrentC.

CurrentC started out with a good idea — to find a way to process payments that did not incur the small percentage transaction charges levied by the credit card industry. Ultimately, this could benefit consumers if the system were to lead to a cultural shift to avoid using credit.

What’s ugly about CurrentC isn’t necessarily the use of QR codes or the security issue that results in consumer data being shared with merchants — it’s that it’s hard to believe that CurrentC is really about making the shopping process better.

At the heart of CurrentC are loyalty accounts and the ability to offer customers coupons, incentives and special deals. Sounds good, right? Not so fast.

Most of the people I know don’t appreciate the loyalty programs they find themselves “forced” into. For instance, to shop at a Safeway grocery store, you either can become a “Club Card” member or you can pay higher prices on many types of food.

Become a member — making it easier for Safeway to track your purchases and build up a customer profile, occasionally offering you extra coupons — or pay hundreds of dollars more in groceries each year. Or drive farther to a different grocery store, burning more fuel and time. Is that a realistic choice for most consumers these days?

Then there are incentives like gasoline discounts. If you buy a bunch of food, you can build up a gasoline discount. Problem is, none of this really adds up to benefit the consumer. Every time I’ve done the math, I would be better off traveling to an employee-owned grocery store — in my case, WinCo Foods — that offers no loyalty program at all. In fact, WinCo doesn’t even accept credit card transactions. No credit card fees results in everyday prices that usually are lower than the other stores’ prices.

The Problem Is the Tracking Data

The problem with CurrentC — at least from my perspective as a person who would prefer not to be tracked, put in a database, and manipulated to buy things — is the data it collects and enables merchants to use under the guise of improving the customer experience.

The fact is, the more data that companies collect around your movements, habits and preferences, the better those companies will be able to pull your puppet strings. We all want to believe that we’re not easily influenced, but the fact is, we’re heading down a path that will treat all of us as the product.

In fact, that’s the conclusion reached by Nick Arnott, a security editor at iMore, who took a closer look at the data CurrentC appears to want to track and manage.

“With CurrentC, you’re not the customer –” he wrote, “you’re the product being sold.”

Great.

The point is, who really cares about all of this? Even with Apple Pay, in order to pay US$5 for a box of cookies and not $7.99 at most stores, I’ll either have to key in my phone number or swipe a loyalty card. Apple Pay is only a big consumer improvement when I’m in some location with a merchant I don’t trust at all just trying to buy a sandwich.

Apple Pay is a small step forward, while CurrentC is a bunch of confusing dance moves that might make loyalty programs easier to deal with while continuing to obscure the big data databases that are building your customer profile.

Why Can’t We Just Have Consumer Choice?

The obviously solution would be to let consumers choose how they pay, and what information they share, and decide for themselves whether personal data tracking is worth paying a lower price for goods and services. Why not?

Here’s why not: The primary goal of CurrentC is not about radically improving the consumer buying experience. If it were, MCX and Walmart, et al, simply would let the value of CurrentC compete for customers — compete for mindshare and consumer love. Instead of excluding others, they would win based on the overall quality of experience.

The problem is, Apple fans are going to love Apple Pay — 1 million of them promptly activated Apple Pay within a few days — and MCX knows it. Hence the exclusive contracts.

This Is All Going to Get Far Worse

Personally, I don’t care how you pay for anything — but here’s what I see happening: Apple Pay and CurrentC will help train consumers to pay with their smartphones. That seems convenient. If I can reduce the size of my wallet, I’m all for that.

The problem is, Apple and other merchants want your iPhones and smartphones to communicate with them — to recognize who you are when you come near. Remember Apple’s iBeacon? The premise for this location-tracking system is to help guide you, or to incentivize you to buy things in retail locations.

Sure, beacons can be used to help a person navigate a museum and learn more about natural history, but they also can be used to prompt a group of baseball fans to leave their seats to take advantage of a special deal on beer and brats to keep the flow of customers at more manageable levels throughout the game. (OK, that actually sounds like a good idea.)

The dark side of all this is that it’s less about helping direct customers to the things they truly need than about manipulating their behavior to get them to spend more and drive up profits.

At best, beacons that communicate with our smartphones will turn into the technology equivalent of open air markets or street vendors hollering at you to get your attention and make a deal. That’s the best-case scenario. You walk into a store that knows you’re a 23-year-old male so you get offered a special deal on the coolest pair of jeans worn by 23-year-old men who bought other pairs of similar jeans… maybe even through other companies. That’s cool, right? No one is pointing a gun at your head and forcing you to buy jeans, right?

Except human behavior isn’t that simple. People are driven by habits, and our habits can be trained — even if we don’t realize we’re being trained. If you haven’t read Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit, you really need to read it. He not only reveals the hard-core manipulations of Target on its own customers, but also teaches you how habits are formed and how you can create your own.

Imagine this: Say you walk into a mall. Your smartphone will alert the mall, and every merchant near you, as well as those who happen to be paying the mall for access to you. It’s 2:30 p.m. Boom, you get an offer for 50 percent off a pumpkin spice coffee with a free cookie. Why that? Before you go shopping, let’s make sure you don’t get tired. Let’s get you all caffeinated and sugared up first.

Thirty minutes after you accept the coffee offer, boom, you get another offer you can’t refuse… but maybe it’s for something you don’t really need. However, the “savings” obscure the real value of the product. Either way, you’re feeling good, so you go check it out. Then you get another offer. Do you even remember what you came to the mall for in the first place? That sugar buzz is wearing off and you’re crashing. It’s now 5 p.m. and you just got two competing new offers, one for a meal in the mall and another to pick up a pizza on your way home. It’ll be ready for you in 18 minutes.

I bet that 80 percent of our population could be persuaded to spend a significantly larger chunk of money on any given day with this sort of power. As an older guy, I can imagine myself turning it off and tuning it out — but what about teenagers? They’re growing up with this sort of technological power, and their habits are ripe for manipulation.

Special coupons and deals manipulate by delivering surprise and delight, commanding attention, and changing habits. Don’t believe me? What do you do when your phone chimes when a new text message comes in? How long can you go before you read it? This is so important that some of us believe we need to receive text messages on our wrists.

So yeah, I like Apple Pay, and I fear the extra ease of information and manipulation that CurrentC may be able to wield over us mere consumers.

Still, no matter which of those systems prevails, as we rush to insert more of our lives into our smartphones, incentives that use beacons and smartphone tracking are coming hard on the heels of these new digital wallets — and I’m not looking forward to it.