Facebook is clamping down on ads and misinformation relating to coronavirus, implementing a policy Head of Health Kang-Xing Jin outlined last month.

Criticism of social media platforms for spreading fear and confusion about coronavirus is rife.

Still, Facebook’s decision-making has raised a few eyebrows, as the coronavirus ad restrictions could be interpreted as limiting free speech in a way that is inconsistent with Facebook’s general practices.

Notably, it has refused to block politicians from spreading misinformation in ads on its platform on the grounds that doing so would hinder free speech.

Curtailing Ads for Fake Cures

“We’re taking steps to stop ads for products that refer to the coronavirus and create a sense of urgency, like implying a limited supply, or guaranteeing a cure or prevention,” a Facebook spokesperson said in a statement provided to TechNewsWorld by company representative Andrea Vallone.

“For example, ads with claims like ‘face masks are 100 percent guaranteed to prevent the spread of the virus’ will not be allowed,” the spokesperson said.

“Not only is this announcement not really new, but it shouldn’t have to exist, as not allowing advertising that’s intentionally misleading or is absolute fraud should not be allowed,” remarked Liz Miller, principal analyst at Constellation Research.

The United States Federal Trade Commission “has some fairly straightforward guidelines on advertising that makes medical claims,” Miller told TechNewsWorld, and can set fines running into the millions of dollars if they are breached.

“Why isn’t Facebook looking to the FTC Act for guidelines and insisting they’re the minimum expectation for all health or medical advertising?” she asked.

Clearing Out Misinformation

Facebook also is removing content that promotes false claims or conspiracy theories about the coronavirus, or false claims about what health resources are available.

It is also taking these actions:

- Labeling misinformation as such and directing users to more accurate information — such as pop-ups redirecting them to the World Health Organization or local or regional health authorities;

- Providing ad credits to WHO and ministries of health across Asia; and

- Sharing aggregated and anonymized mobility data and high-resolution population density maps with researchers at universities to help inform their forecasting models for the spread of the virus as part of Facebook’s broader “Data for Good” program.

A Concerted Effort

Facebook might be ramping up its efforts in the wake of a meeting it hosted at its Menlo Park campus between WHO and 12 high-tech firms, including Google, YouTube, Amazon, Twitter, Salesforce, Verizon, Airbnb, Twilio and Dropbox.

Apple, Lyft and Uber reportedly were invited but did not attend.

The meeting focused on how the attendees were working to stop the spread of misinformation.

The group will meet every few months.

Prior to the meeting, Twitter said it was “not seeing significant coordinated attempts to spread disinformation at scale” with respect to coronavirus, but that it would remain vigilant and would remove people tweeting misinformation from its service.

Speech Is Not Free

Facebook’s actions against fake ads and misinformation about coronavirus raise questions about its support for freedom of speech, which was its argument for refusing to take action against misleading statements politicians might post on its platform.

“Facebook’s position certainly suggests that if the penalties were higher for fake political news, Facebook would be more aggressive at moderating that content as well,” said Rob Enderle, principal analyst at the Enderle Group.

“This shows they can do it, and that if the risks are high enough for Facebook, they will do it,” he told TechNewsWorld.

On the other hand, “false medical claims do potentially carry liability back to Facebook, whereas false political claims do not,” Enderle pointed out. “That’s probably dictating Facebook’s behavior.”

Facebook “is not a free speech zone,” said Mike Jude, research director at IDC.

“Even its contract claims that it reserves the right to exclude any commentary that violates its rules. If you put any limits on speech it’s no longer free,” he told TechNewsWorld.

Facebook could report people advertising purported cures for coronavirus to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Jude said, “but that would be the camel’s nose in the tent when it comes to social media regulations, and they probably don’t want that.”

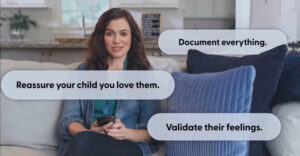

Clamping down on ads is different from restricting misinformation spread through user posts and conversations, Constellation’s Miller noted.

The latter “falls under the question of whether an individual user has the right to spread content that is based on misinformation,” she pointed out.

“In that situation, Facebook must tread a fine line between free speech and giving the community the opportunity to debunk misinformation, and banning content,” Miller observed.

Opening a Can of Worms

“Moderating is a slippery slope,” remarked Enderle. “What constitutes the truth for one group may constitute a lie for another, and sensibilities concerning what is appropriate content vary widely.”

Facebook’s fact-checkers may be having problems enforcing its rules in a logically consistent way, Jude suggested.

“Once the body of rules becomes so complex that a human can’t articulate how it’s applied consistently, the whole edifice collapses,” he added.

“Remember Robocop 2, when the committee came up with all the rules he had to follow and had them hardwired in? When he saw a crime he couldn’t function because of all the contradictions built into the rule book,” Jude said.

Facebook “is now the committee trying to program its version of Robocop,” he suggested, “trying to contain badness with a rule book that has too many internal inconsistencies. Every new rule they adopt just makes it worse.”