Facebook is enmeshed in yet another brouhaha over its advertising policies, but this time it’s not the users making a fuss — it’s the advertisers.

Major clients such as Nissan and Nationwide recently pulled the plug on their Facebook campaigns after their ads showed up next to objectionable, sometimes downright hateful, content.

It’s not that users have been silent about the offensive posts. The advertisers were prompted to act following an outpouring of ire for allowing their ads to be placed next to content glorifying sexual violence or gay bashing.

Advocacy groups had also been lobbying Facebook to remove some of these posts in recent months but apparently to no avail.

Got Their Attention

Facebook reacted almost immediately to the loss of advertising, however, publishing a statement on Tuesday clarifying its stance on controversial posts and hate speech, and explaining why it took so long to remove offending content.

Facebook wants the site to be a place where thoughts and exchanges are freely expressed, it said, even if that means some of user posts may be offensive or controversial.

However, Facebook will not tolerate speech that is directly harmful, and it prohibits “hate speech.”

Facebook acknowledged that it has been lax in identifying and removing hate speech, particularly around issues of gender-based hate.

“In some cases, content is not being removed as quickly as we want,” said Marne Levine, VP of global public policy. “In other cases, content that should be removed has not been or has been evaluated using outdated criteria.”

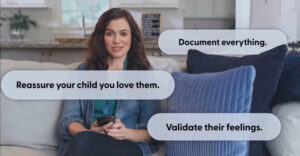

Facebook has set out a series of steps to ensure that its safeguards work better, including updating training for the teams that evaluate reports of hateful speech, and establishing more formal lines of communications with representatives of women’s groups and other such associations.

Tighter Targeting?

From a practical standpoint, there are other measures Facebook can take to ensure that all parties — or at least the advertisers — are kept happy.

For one thing, it could deploy tighter targeting, suggested Rob Enderle, principal of the Enderle Group.

“If you tightly target ads and content to users, then you are far less likely to put content and ads together that don’t belong together,” he told TechNewsWorld.

While the tighter targeting could be automated to some degree, removing content requires human interaction at some point in the process, noted Charles Palmer, associate professor of new media at Harrisburg University of Science and Technology.

“I sympathize with Facebook, because identifying and removing hateful speech and images is a manual process and it can’t be done quick enough for the general public,” he told TechNewsWorld. “Facebook is relying on the public to report inappropriate images, but that is a slow and tedious process. “

Not a First Amendment Fight

One thing this episode is not is a First Amendment fight.

The First Amendment only limits the actions of government, Martin Margulies, professor emeritus at the Quinnipiac University School of Law, told TechNewsWorld.

“Far from curtailing First Amendment rights, the advertisers have a First Amendment right of their own — to ask Facebook to reject or distance them from speech that they deem offensive,” he continued.

“And Facebook, a private actor, likewise has a First Amendment right to decide how to respond — by rejecting the advertisers’ pressure or by yielding to it. They do not violate the First Amendment if they choose to do the latter,” Margulies pointed out.

Further, there are no laws against so-called hate speech, he added. “Such laws, when enacted, have uniformly been pronounced unconstitutional under the First Amendment.”