The 102nd running of the longest sporting event in theworld, the Tour de France, begins Saturday. The race first took place in 1903, and it hascontinued every year since, except during WWI and WWII.

In the 112 years since that first race, the technology utilized by the riders has changed dramatically.

Today, the racers ride bikes with frames made of advanced carbon fiber. Theyhave a total of 22 gears to help climb mountains and sprint to thefinish line, and they can communicate with their team managers over race radios.Miniature GPS-powered cycling computers are used to track speed,cadence, calories burned and, of course, distance.

All this technology is meant to give the elite riders a winning edge,but as with auto racing, the machine — in this case, the bicycle –is just part of the story. It is the rider who has to havethe skills and determination to reach the finish line, but cyclingtechnology has taken the race in directions that early riderswould hardly recognize.

The Evolution of Bicycle Technology

When the first tour started outside Paris in 1903, the racers usedheavy steel frame bicycles that had just a single gear. Bulky toe clips — which helped hold the riders’ feet on the pedals — were the cutting-edge technology of the day.

A decade later,the brakes were refined and gears were added, yet riders still had tostop often and even dismount the bicycle to change gears! It wasn’tuntil 1937 that the derailleur was introduced, which allowed riders toshift gears while pedaling.

Steel was the de facto material for most bicycle components untilthe 1980s, when companies such as Italy’s Colnago began to seekalternatives that were lighter and more durable.

However, itwasn’t until the 1990s that aluminum, titanium and carbonfiber made an appearance. Carbon fiber won out, and1998 was the last year that a non-carbon fiber bike was ridden inthe Tour de France.

In the early days, riders would head out and not be seen except at various checkpoints along the race route.Communication with the riders was introduced in the1990s, when Motorola sponsored a pro cycling team. Now,every rider is allowed to wear a race radio that allows forreal-time communication with a team director.

The use of race radios has drawn some criticism, however, on the grounds that it allows those in thelead to get too much information on the state of the peloton — thepack of riders racing behind them.

The Modern Frame

Perhaps the biggest advancement in cycling technology has been in thematerials. To many, a bicycle is essentially a frame with wheels, aseat and other parts attached to it. At its simplest, this isfairly accurate. The frame has widely improved over theyears, though, and today’s carbon fiber is leaps and bounds better than the carbon fiber that first appeared almost two decades ago.

“There is something to be said” for the type of carbon fiber in use today, according to Dan Cavallari, who writes for the bicyclingracing trade magazine VeloNews. Today’s carbon fiber frames are different from those used as recently as five years ago, he pointed out.

“Everything is [aerodynamic], as opposed to just looking like steeltubes that we saw 10 years ago,” Cavallari told TechNewsWorld.

Each year, the carbon fiber improves in new ways, but its greatestbenefit may be in the weight it saves, while also providing a betterride for the Tour de France racers — who spend upwards of five hours a day on thebike for nearly a month!

“Carbon fiber was initially explored as a material for bike frames dueto its extreme low weight,” said Andrew James, BMC road productmanager. “As experience grew, however, we’ve begun to realize its truebenefits lie in customization. Not only can we achieve low weight, butwe can tune for compliance, stiffness, vibration absorption andaerodynamics.”

Many of the world’s carbon fiber bicycles are made in China,which has become the leading producer of carbon fiber, but BMCcontinues to design and build its frames in-house at its ImpecAdvanced R&D Lab in Grenchen, Switzerland.

The company’s uniquedesigns likely contributed to Cadel Evans’ 2011 Tour de France win, andthis year American-born BMC Racing Team rider Tejay van Garderen hashis eyes on the podium as he rides the company’s latest bicycle.

Just as van Garderen has spent countless hours training, the makers of hisbicycle have spent countless hours perfecting its design.

“Our ACE (advanced composites engineering) technology allows us toiteratively produce thousands of virtual prototypes — 34,000 in fact,in the case of the Teammachine SLR01 (pictured above), which will be raced in the Tour –optimizing tube shapes, cross sections and carbon fiber layups,”James told TechNewsWorld. “We are then able to quickly and producerideable frames to test out new innovations.”

Shifting Gears

With the advent of the derailleur, a bike’s gears could be changed bythe use of a simple lever, which originally was mounted on the frame’sdown tube. This was an improvement over prior systems, whichrequired that riders stop and reach down to the wheel’s hub to changegears, but the frame-mounted lever still required riders to take theirhands off the handlebars and brakes — not to be recommended on a fastdescent in the Alps!

In the early 1990s, Shimano introduced its STI (ShimanoTotal Integration) system, which combined the braking and gear-shifting controls in the same component. That allowed riders toshift gears without having to remove either hand from the bars, whichhas made cycling safer — not just for the pros, but for amateur cyclingenthusiasts as well.

The technology further has been enhanced by theintroduction of electronic shifting, which provides smoother and moreaccurate changing of the gears. The downside is that there is one morething that can go wrong during the race. For this reason, theelectrical systems have not been fully embraced by all the riders. However, should the electrical systemfail or the battery die, there is a manual override.

Tracking Progress

Radio communication is just one game-changer for the race. Old analog speedometers have given way to digital cycling computers, and the advent of GPS has allowedriders to cut the cord while tracking speed, distance,elevation, and even calories burned.

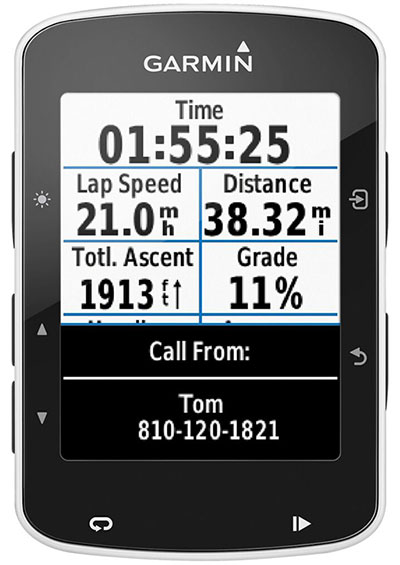

At this year’s Tour de France, Team Cannondale-Garmin’s racers willutilize the Edge 520, the first GPS bike computer with Strava LiveSegments. It is the first GPS bike computer that allows users toupload segments from Strava, an online fitness-monitoring service, andallow riders at all levels to compete for virtual titles such as Kingor Queen of the Mountain.

“The Edge 520 taps into cyclists’ competitive edge and offers them thelatest in innovative training tools,” Dan Bartel, Garmin vicepresident of worldwide sales, told TechNewsWorld.

The mini-cycling computer offers a high-resolution color display,and it is GPS- and GLONASS-compatible.

It features advanced analysis capabilities that include time intraining zone and functional threshold power, and it is compatible withindoor trainers. It also offers riders at home the ability toshare their workout readings via social media.

Aside from tracking progress during training and during a race, which iscrucial, there is one other metric that is important atthe competitive level: power output. This data helps racers trainbetter and can quantify effort during a ride. It helps racers determinethe number of calories they may need to consume throughout anevent so as not to “run out of fuel,” so to speak.

“Power is a true quantification of the work they do while pedalingtheir bike,” said Matt Pacocha, spokesperson for Stages Cycling, adeveloper of cycling power meter technology.

“It’s best used in tandem with other metrics, like heart rate, in orderto give a full picture of a rider’s effort and efficiency,” Pachochatold TechNewsWorld.

The power meter, which is a Bluetooth-enabled device that mounts tothe crank arm above the pedal, sends data to a rider’s cyclingcomputer or mobile phone. It can be used in training leading up to abig race, helping riders understand their potential.

“Savvy coaches will build training workouts that are based on knownweaknesses or even strengths from their race data,” added Pachocha.”Then, once the workout is developed, the rider can use their powermeter to precisely follow their coach’s instructions: This is called’prescription training.'”

The Winning Edge

At the end of the day, it is the rider who has to do the pedaling for 21 days and more than 2,000 miles.

It’s true that “technology is changing the race,” as VeloNews’ Cavallari pointed out.

Still, “no matter what you throw on the bicycle, the rider is the engine,and he has to be the strongest and fastest one out there,” headded. “Technology doesn’t change this fact. The winner is the guy whotrained for years to get where he is, and all the technology in theworld won’t make enough of a difference.”

A few corrections should be made here. Aluminum did not make its first appearance in the 1990s. I have an all-aluminum bicycle made in 1975. In fact an earlier version of this bicycle won the Tour de France. The components are also aluminum, but were made by an Italian company called Campagnolo, not "Colnago." When this bicycle was set up for racing it had 12 gears, a non-steel, composite gear cluster and what they called "sew up" tires. New, it weighed 18 pounds, which is competitive with the lightest bikes available today. And I would be willing to bet that in spite of all of the tech improvements, the actual non-steroid performance times have only marginally improved, and a good share of the improvement came from improved training, not higher-tech bikes. Ferrari made some pretty fast cars in 1975 too.