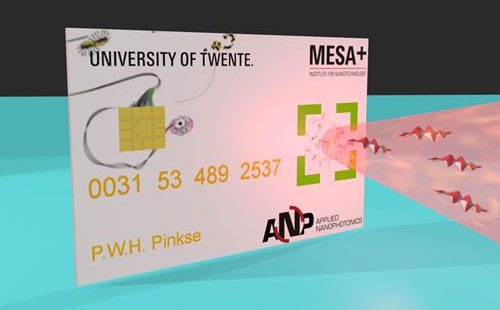

Researchers at the University of Twente and the Eindhoven University of Technology have come up with what they claim is an unprecedentedly secure way to authenticate credit cards, IDs, biometrics, and parties involved in quantum cryptography.

The method — quantum-secure authentication of optical keys — basically consists of sending a beam of light at cards treated with a special paint and using the reflection as the authentication mechanism.

It employes coherent states of light with a low mean photon number — loosely speaking, that means there’s lots of space for the photons to bounce around in.

Photons can be in more than one place at a time, so when the cards reflect the beam, there will be more dots of light sent back than there are photons, and attackers won’t have enough data to measure the entire pattern.

The solution is easy to implement with current technology, and it does not depend on the secrecy of any stored data, the researchers claim.

However, “we’ve left in place unsecure magnetic card readers a decade or more after we knew they weren’t secure enough,” observed Rob Enderle, principal analyst at the Enderle Group.

That behavior “could limit adoption of any new, more secure technology for cards,” he told TechNewsWorld.

Details on the Research

The researchers used cards coated with a layer of white paint containing millions of nanoparticles that bounce incoming light particles between them until the light escapes.

They also used two spatial light modulators, a pinhole and a photon detector. One SLM transformed incoming light into the desired challenge wavefront and sent it to the card. The corresponding reflected response and the challenge were stored in a database.

Each challenge-response pair currently requires 20 KB of memory; the 50-MB database holds 2,500 pairs.

Every superposition of challenge-response pairs itself is a challenge-response pair, adding a further layer of security.

The second SLM added light reflected back from the cards to the conjugate phase pattern of the expected response wavefront only if the response was correct.

The correct responses were then sent to a lens behind the second SLM that focused them onto a photon detector to authenticate them.

Technical Details of the System

The challenges in this system are high-spatial-dimension states of light with few photons and the response is a bunch of light dots in a speckled pattern. The pattern created depends on the challenge and the positions of the paint particles.

Each challenge in the experiment was described by a 50 x 50 binary matrix, with each element corresponding to a phase of either 0 or Pi.

“We needed to make the illumination pattern complex enough to make sure that the number of photons is lower than the number of pixels in the image,” research leader Pepijn Pinske, Ph.D., told TechNewsWorld.

The first SLM transforms an incoming plane wavefront into a challenge wavefront selected at random from the database. Since the challenge is dynamically created and exists only after the transformation, it cannot be intercepted.

The response is recorded in a phase-sensitive way.

The light source used in the research was an attenuated laser beam chopped into 500 ns light pulses each containing 230 plus or minus 40 photons.

The database contains 2,500 challenge-response pairs because “the diffraction limit sets an upper limit to the number of separate spots you can write on a small surface,” Pinske said. “2,500 is about the maximum for the chosen area.”

Pluses and Minuses of the System

The challenge-response database could be hacked, but “the keys would not be in a form that could be digitally reproduced and therefore [would be] virtually useless to the attacker,” Adam Kujawa, head of Malware Intelligence at Malwarebytes, told TechNewsWorld.

“There are simply too many particles which are too small that need to be positioned with too high accuracy [to let anyone make a physical copy of the database],” Pinske said.

Further, hackers can’t cycle through the challenge-response pairs and return the appropriate response because the security doesn’t exist within the challenge response but in the light photons of the key, Kujawa said.

“The verifier picks a random challenge light pattern which cannot be read out since there aren’t enough photons in it to measure the pattern,” Pinske explained. That, combined with the technological impossibility of copying the database, makes the system secure.

“I’m concerned that the output could change depending on environmental conditions or just over the life of the electronics,” commented Jim McGregor, principal analyst at Tirias Research.

Nothing’s Impossible

The system could be broken by using a passive linear optical system that automatically transforms any challenge into the correct response, Pinske said. “That is very close to making a physical copy of the key.”

QSA will not solve all a user’s security needs, he cautioned. “In the end, an unclonable key can be stolen, and we offer no solution to that.”

Still, “we do improve one aspect in a very fundamental way: the physical key,” Pinske pointed out. “That is already quite a feat.”

Security “must be done in layers, because different [types of data] require different levels of security and because you have limitations in memory, performance, bandwidth and power at different levels in the value chain,” McGregor told TechNewsWorld.

Possible Uses for the QSA

Coupling QSA with biometrics “would add significantly to the difficulty” of using stolen cards, and geolocation tracking would invalidate it if it were used by a thief in a location away from the legitimate cardholder, Enderle suggested.

“Apple could adopt this technology, which is well beyond that currently in use, but I would expect the cost to be prohibitive,” he mused. It would probably show up in big pharmaceutical firms and in government or military installations “where security funding is generally greater.”

QSA also could be used to authenticate paintings, Pinske said, and “we are even wondering if the scattering [of light] from teeth could be used as a kind of biometric version of QSA.”